A short – but longer – history of the draft horse

W.J. Boonstra, Uppsala University

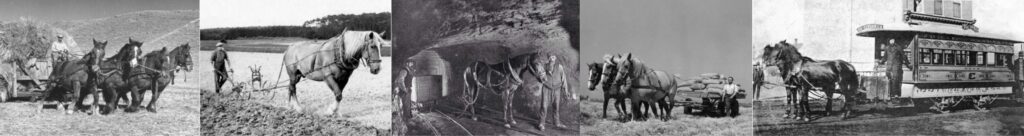

The draft horse is most often thought of as a relic of the past: once upon in time these horses were used in farming, but during the first half of the 20th century got replaced by tractors (Smil 2000).

This common interpretation is giving short shrift to the long and varied working relation between people and horses, the agrarian development that was realized with horses and horse-drawn machinery, and the societal progress that sprang from it (Clutton-Brock 1992; Greene 2008; Mitchell 2015; Raulff 2017). It also dismisses out of hand the central function horses continue to have for farmers around the world, and more so their potential for sustainable and regenerative agriculture now and in the future (Leslie 2015).

For most of our agrarian history, labor on farms was provided for by human labor. Later farmers started to use animals, such as oxen. Horses were often owned by elites and used in warfare. The horse as the main provider of traction and labor on farms accelerated in the 19th century. During that time horses became more affordable, but also more desired (Greene 2008: 12). The horse provided labor as well as prestige in modernizing society that enabled rambunctious economic growth and social mobility.

Horses, together with donkeys and cattle, share a number of characteristics which make them the most used animals for (farm)work [1] worldwide. They are strong enough, but not too strong to control. They are plant eaters. They are herd animals and as such attuned to hierarchies and power, accepting humans as leaders and able to bond with them. They can breed in captivity. Their fight-flight instincts are evened out. They are not territorial nor require distinct places or size of territory for mating or diets (Greene 2008: 13–14).

The 19th century became the century of the horse. The growing economic importance of horses on farms, but also in transportation, and as a source of labor in the treadmills of expanding industries, triggered the development and innovation of horse-drawn machinery and carts as well as harnesses. And all these horses used in the growing global economy elicited the work and knowledge of engineers, farriers, veterinaries, and others that supported the animal in its work.

The abundance and importance of draft horses on farms diminished quickly after the first half of the 20th century when tractors became more affordable and widely available. Most histories of draft horses stop here, but stop short. Despite ongoing mechanization and technologization of farm labor (van der Ploeg 2013), draft horses remain in use worldwide.

For many smallholders in the global South horses and donkeys continue to be an important labor source for traction and transportation (Blench 2015). But also groups of smallholders in the global North rely on help from horses in agriculture, gardening or forestry (Leslie 2015). Draft horses match well with a scale and style of farming that aims for self-reliance (Berry 2017), regeneration of natural resources, use of renewable energy (Rydberg and Jansén 2002), and sustainable production and consumption (Berry 2001).

The history of the draft horse has not ended yet; the draft horse has been key in keeping smallholders and sustainable farms in business, until now and into the future.

References

Berry, W. 2001. The whole horse. In: The new agrarianism. Land, culture, and the community of life, Eric. T. Freyfogle (ed.), pp. 63-80. Island Press Shearwater Books: Washington.

Berry, W. 2017. Horse-drawn tools and the doctrine of labor saving. In: The world-ending fire. The essential Wendell Berry. Selected and with an introduction by Paul Kingsnorth, pp. 151-158, Penguin Books: London.

Blench, R. 2015. A history of animal traction in Africa: origins and modern trends. In International Workshop: Construction of a Global Platform for the Study of Sustainable Humanosphere. Available at http://www.rogerblench.info/Ethnoscience/Animals/Livestock/ Blench%20Kyoto%202015%20plough%20text.pdf

Clutton-Brock, J. 1992. Horse power: A history of the horse and donkey in human societies. Natural History Museum: London

Greene, A.N. 2008. Horses at work: Harnessing power in industrial America. Harvard University Press: Harvard.

Leslie, W. 2015. Horse-powered farming for the 21st century. A complete guide to equipment, methods, and management for organic growers. Chelsea Green Publishing: River Junction.

Mitchell, P. 2015. Horse Nations. The worldwide impact of the horse on indigenous societies Post-1492. Oxford University Press: Oxford.

Raulff, U. 2017. Farewell to the horse: A cultural history. Liveright Publishing: New York.

Rydberg, T. and Jansén, J., 2002. Comparison of horse and tractor traction using emergy analysis. Ecological Engineering 19 (1): 13-28.

Smil, V. (2000). Horse power. Nature 405 (6783): 125-125.

van der Ploeg, J.D. 2013. Peasants and the art of farming. Fernwood: Nova Scotia.

[1] Besides horses, donkeys and cattle, other animals used for work include camels, Ilamas/alpaceas, reindeer, yak, asses (donkeys), pigs, sheep, goats and several kinds of cattle (including water buffalo). But these other animals are not used as widely due to limitations in terms of their strength, temperament, behaviour, amongst others.